In the US, pandemic preparedness has long been neglected among national security concerns.

One would think that the harrowing experience of the past year would change that. But in light of recent reports that the $30 billion in pandemic preparedness funding proposed in the American Jobs Plan might be cut to $5 billion in the bipartisan, negotiated compromise, it’s not clear whether Covid-19 has been enough to teach the US its lesson.

For decades, public health policy experts have tried to convince the US government to take real steps to prepare for a respiratory pandemic.

“It is the prospect of another such pandemic [like the Spanish flu] — not a nuclear war, or a terrorist attack, or a natural disaster — that poses the greatest risk of a massive casualty event in the United States,” Ron Klain, now the White House chief of staff, argued in Vox in 2018.

“All of this stuff was a no-brainer 30 years ago,” Amesh Adalja, at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told me. “We’ve been briefing Congress, we’ve been doing this since 1997. We were ignored. All those glossy reports telling people what to do? Those gathered dust in someone’s desk drawer.”

In 2020, the world paid the price. What the pandemic experts had warned of came. It killed millions worldwide, devastated the global economy, and disrupted billions of lives. And not only is Covid-19 still circulating, there’s every reason to believe a worldwide catastrophe like it can and will happen again.

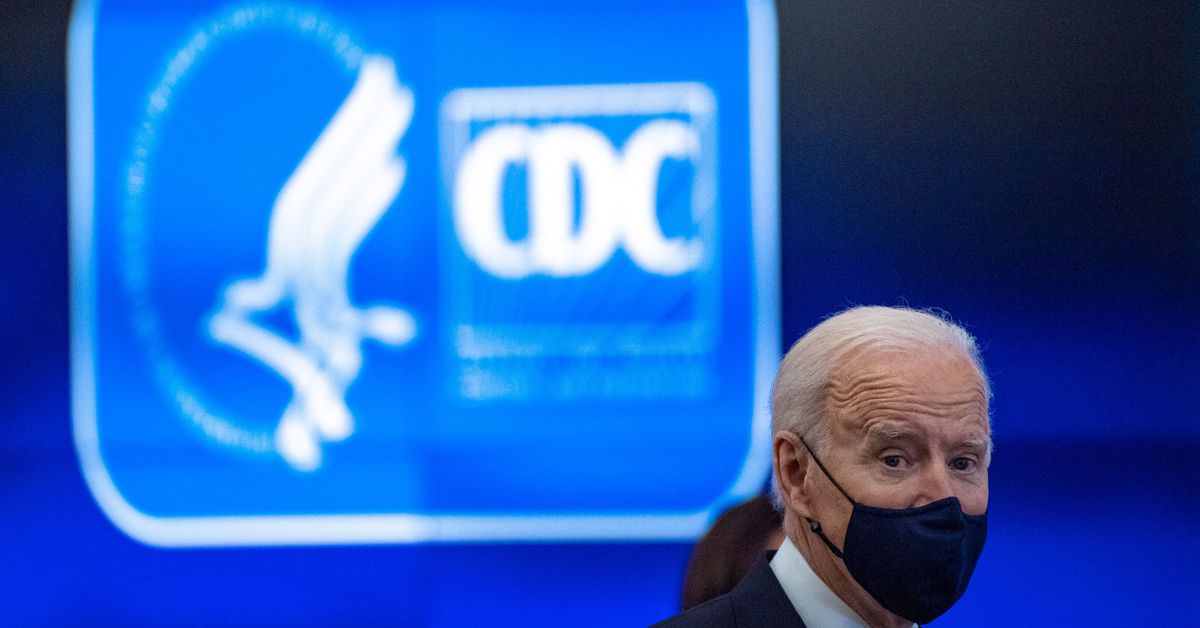

But in an op-ed published earlier this week, Tom Frieden, former director of the CDC, and former US Sen. Tom Daschle reported the potential cuts to pandemic preparedness in the American Jobs Act, President Joe Biden’s signature infrastructure plan.

If true, it underscores a depressing fact: that our policymakers haven’t quite grasped the scale of what’s required to fight the next pandemic.

The original $30 billion Biden asked for is already too small as it is. By the time all is said and done, it is estimated Covid-19 will have cost the world between $16 trillion and $35 trillion. The next pandemic could be even more devastating.

Facing risks of that magnitude, $30 billion is a pittance. Some experts suggest nothing less than an Apollo program for pandemic prevention, with $20 billion a year in spending for 10 years. If such a project made the next pandemic even moderately less bad, it would abundantly pay for itself. If it prevented it, it’d be one of the best investments in history.

Policy is often plagued by short-termism. It’s too easy to think ahead only to the next election cycle, and to think of anything whose benefits are long term and uncertain as “nonessential” and subject to budget cuts whenever convenient. But that short-termism is a betrayal of our future. If Covid-19 hasn’t taught us that, it’s not clear what will.

The shortsightedness on pandemic prevention is especially galling because pandemics are absolutely preventable.

“Outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional,” Larry Brilliant, who worked on global smallpox eradication, famously said.

Given the human population worldwide, it’s inevitable that new diseases will emerge — jumping from animal hosts or evolving as particularly virulent strains of endemic diseases. But when that happens, if everything goes right, we can stop those diseases from becoming the next pandemic.

The first step is inventing potential vaccines and antiviral treatments, which we can do even before a virus hits us. “We know that there are certain families of virus that we know are more likely to produce a pandemic pathogen,” Adalja told me. Coronaviruses, for example, were on researchers’ radar even before SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes Covid-19) emerged because of SARS-1 and MERS, both of which have led to deadly outbreaks in Asia.

Despite the potential for a new coronavirus to emerge, the US did not make the massive investments in developing antivirals and vaccines against coronaviruses that would, in hindsight, have been useful to have. But even the smaller investments which the country did make into SARS-1 and MERS research paid dividends.

“The fact that we had vaccines within a year is testament to the work on SARS and MERS,” Adalja said. “The SARS and MERS work did produce information, such as the spike protein is important for immunity — so they knew right away, we need a vaccine against the spike protein. Even though we didn’t have any SARS vaccines or any MERS vaccines ready to go, that early work was useful.”

The government could fund such research into every class of virus that is considered likely to produce a potentially pandemic pathogen.

And the breakthroughs that would no doubt come from that research wouldn’t only protect humanity against pandemics. They might also lead to a vaccine for the common cold or for the flu, or to new antivirals that reduce the death toll of viral illnesses.

The next step is disease surveillance — observation of the spread of respiratory illnesses around the world — so that when a new disease emerges, we get an accurate picture of its spread right away.

By late December 2019, hospitals in China were already seeing an upswing in severe respiratory illness cases. Countries with effective disease surveillance, like Taiwan, jumped into action then, with public health officials getting on airplanes from Wuhan to screen passengers — weeks before China officially acknowledged that an outbreak was underway.

One promising part of that is what’s called pathogen-agnostic screening. When a person goes into the doctor’s office with a respiratory illness, they will get tested for Covid-19. If they don’t have Covid-19, they might get tested for the flu — or they might not. Many people are assumed to have the flu without screening.

The technology exists to change that. “The technology is now to the point where you don’t just go test for Covid, yes or no, test for flu, yes or no. We can test for hundreds of pathogens that cause respiratory diseases,” Andy Weber, the former US Assistant Secretary of Defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological defense programs, who now works on biosecurity for the Council on Strategic Risks, told me.

That means we have the ability to develop a system where if someone comes in sick, they’ll get tested automatically. And if they’re sick with something unprecedented, their doctors will know right away.

“If the Chinese had had this in place, it would’ve been nipped in the bud,” Weber said.

That tactic needs to be combined with improved state and local public health infrastructure. During Covid-19, state and local contact tracing was quickly overwhelmed. States didn’t have testing or quarantine capacity.

“States could not hire contact tracers,” Adalja said. “They were using very primitive kinds of pen-and-paper contact tracing. They have poor communications with hospitals and health care facilities. They’re constrained with hiring people.”

As a result, the US ended up fighting the pandemic in the dark.

If the funding proposals now under consideration had passed two years ago, the US “would have had public health departments that are able to really rapidly respond, we would have had tests that are available earlier,” Frieden told me.

“We would have known a month earlier that Covid was spreading in New York City. We also would have been able to do much better contact tracing, so we would have understood more and earlier where Covid was spreading and how to reduce that,” he added. “We would have had better infection control, so doctors who are dead today wouldn’t be dead.”

Critical to changing all of that is more funding.

In 2001, shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, someone mailed anthrax — a deadly bacterium — to the offices of several US senators and several media outlets. Five people died, and interest in biosecurity soared. For a few years, Congress spent lots more money on preparing America for identifying and combating infectious diseases. Biodefense funding spiked to $8 billion from $600 million.

But then health security saw year after year of cuts, and it was back down to about $1.5 billion by 2018.

That dynamic has been dubbed by experts the “cycle of panic and neglect.” When bioterrorism or a potential pandemic hits the headlines, readiness gets funded. When a few years have gone by, it stops.

And right now, if reports of the funding cuts are to be believed, we’re doing even worse than that: racing straight to “neglect” before the pandemic has even ended.

Ending the threat of pandemics in the United States means a change in approach. Weber’s proposal is a “10 + 10 Over 10” plan — that’s $10 billion to the Department of Defense for biological threat preparedness and $10 billion to the Department of Health and Human Services to prevent biological threats in the future, over 10 years. That would allow for building mRNA vaccine factories that crank out vaccines year-round; upgrading public health infrastructure, testing, and reporting systems; and researching the biggest threats ahead so America can be prepared for them.

That might sound like a lot of money. But it pales in comparison to the human and economic cost of normal infectious diseases, let alone Covid-19, let alone the diseases much worse than Covid-19 that have the potential to be around the corner. According to one study, the annual economic burden of influenza alone in the US is estimated at $11.2 billion. Covid-19’s toll worldwide has been estimated at perhaps $22 trillion. And future pandemics could be worse: As Frieden points out, “Covid kills one out of 200 people,” and has killed millions to date. “There are diseases that kill one out of two people,” he told me.

“We have to do everything we can to make sure that this is the last pandemic we have to deal with,” Weber argued. With that goal even potentially in reach, it seems unwise to try to scrimp on the science and health work that is needed to reach it.

What’s presently under discussion in Congress is considerably less ambitious than Weber’s proposal. The American Jobs Plan, at least in its original form, includes $30 billion in pandemic preparedness spending — but it’s a one-off allocation, not a permanent new commitment to fighting pandemics.

Still, there’s no disputing that it would make a huge difference. It would allow for foundational research like what led to mRNA vaccines — and it’d be a step toward meeting the administration’s goal to have the capacity to make enough vaccines for the whole population in a matter of weeks. It would revamp the systems that every American has witnessed failing to protect them during the pandemic.

“Every American has been touched by this, and it was completely and entirely a failure of government,” Adalja told me. “This would have been preventable with the correct government actions.”

And that $30 billion could, ideally, be a down payment on further commitments. A dozen senators have cosponsored the Public Health Infrastructure Saves Lives Act, which would commit $4.5 billion a year to pandemic prevention. With such commitments, Covid-19 could genuinely be a turning point for how we fight disease.

That’s why it’s so depressing to learn that the way negotiations are currently trending, a one-time boost of $30 billion — already inadequate — might be whittled down further.

It’s impossible to see that as anything but an utter failure of vision — an inability to believe that doing better than the country’s disastrous Covid-19 response is even possible. There should be broad, bipartisan agreement that what the nation has gone through over the last year must never happen again — and there should be broad awareness that, in many ways, the world got lucky with Covid-19: The next pandemic could be far deadlier or particularly dangerous to children or harder to vaccinate against.

A government focused not just on the present but on the risks its citizens face 10, 20, or 30 years down the line should be willing to make a down payment on a better future. But it’s also entirely possible that the country needs an even more expensive lesson before it learns anything.

source https://www.vox.com/22589042/covid-pandemic-preparedness-vaccines-treatments-funding

Post a Comment