Radar images of the Mauritanian desert have revealed a river stretching for more than 500km and suggest plants and wildlife once thrived there.

A vast river network that once carried water for hundreds of miles across Western Sahara has been discovered under the parched sands of Mauritania.

Radar images taken from a Japanese Earth observation satellite spotted the ancient river system beneath the shallow, dusty surface, apparently winding its way from more than 500km inland towards the coast.

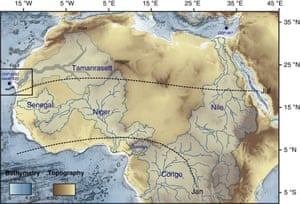

The buried waterway may have formed part of the proposed Tamanrasett River that is thought to have flowed across parts of Western Sahara in ancient times from sources in the southern Atlas mountains and Hoggar highlands in what is now Algeria.

The French-led team behind the discovery believe the river carried water to the sea during the periodic humid spells that took hold in the region over the past 245,000 years. Water may last have coursed through the channels 5,000 years ago.

The river would have helped people, plants and wildlife to thrive in what is now desert land, and would have carried nutrients crucial for marine organisms far into the sea. Were it still flowing today, the river system would rank 12th among the largest on Earth, the researchers write in the journal Nature Communications.

Images taken from the satellite revealed that the hidden river beds aligned almost perfectly with a huge underwater canyon that extends off the coast of Mauritania into waters more than three kilometres deep. First mapped in 2003, the Cap Timiris Canyon is 2.5km wide and a kilometre deep in places.

The outlines and the main course of the proposed Tamanrasett River are drawn in blue and grey, respectively. The newly identified river and the Cap Timiris Canyon are in dark blue on the far left of the map. Photograph: Nature Communications

Russell Wynn at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton was among the researchers who created the first 3D map of the canyon from the German Meteor research vessel. Sediment cores brought up from the canyon bottom contained fine-grained river-borne particles that suggested a massive river had first formed, and later fed into, the deep channel carved into the continental shelf.

“It’s a great geological detective story and it confirms more directly what we had expected. This is more compelling evidence that in the past there was a very big river system feeding into this canyon,” said Wynn, who was not involved in the latest study. “It tells us that as recently as five to six thousand years ago, the Sahara desert was a very vibrant, active river system.”

In full flow, the river would have carried organic material from the land out into the ocean, where it sustained a rich ecosystem of filter feeders and other organisms in the canyon. But the river was destructive too, occasionally sending rapid, turbulent rushes of water and sediment down the canyon. Similar flows are still active off the coast of Taiwan today, and hold enough power to destroy submarine cables and other infrastructure.

“People sometimes can’t get their head around climate change and how quickly it happens. Here’s an example where within just a couple of thousand years, the Sahara went from being wet and humid, with lots of sediment being transported into the canyon, to something that’s arid and dry,” Wynn said.

-- Delivered by Feed43 service

Post a Comment