Melissa Danowski, an appellate attorney in New York state, is a feminist. She and her husband have two young sons and have usually divided household and child care responsibilities equally. But when the pandemic came and shuttered schools and child care services, Danowski’s feminist ideals smashed into reality. Like women across industries and regardless of experience and position, she makes less money than her husband. So as many Americans did at the time, her family made a simple economic calculation: She had to take care of the kids.

The only way Danowski could meet the strict court deadlines for her job was by regularly working on weekends and through the night after her kids went to sleep.

“It meant my own self-care and basic needs — sleep, exercise, downtime — came dead last,” she said. “I usually thrive under pressure, but this translated to frequent meltdowns, panic attacks, and a whole new level of stress I never before experienced.”

She added, “I would rather retake the bar exam for two weeks straight than have to repeat the balancing act I miraculously achieved for months on end last year.”

Danowski is one of millions of working American mothers who had a similarly hellish experience over the past 17 months. And, unlike many, she was fortunate enough to be able to keep her income and to work in the relative safety of her home.

Still, nearly two dozen white-collar women Recode interviewed in recent weeks said working from home during the pandemic stretched them beyond their limits.

Mothers working from home during the pandemic have reported higher rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness than fathers. Last year, 3 million women dropped out of the workforce — and 1.6 million of them still have not returned. That means companies have lost employees with valuable perspectives that have been proven to make companies more innovative and profitable. It also shrinks the talent pool for companies who are desperately seeking workers.

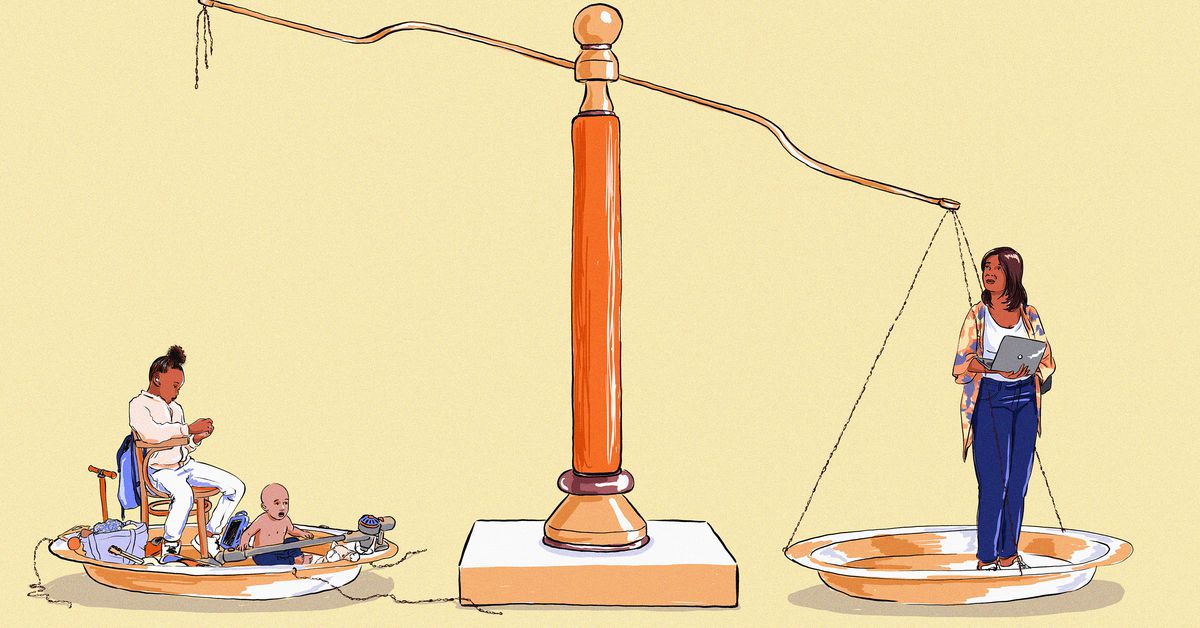

That all creates an unfolding crisis, not only for women and their families, but for society and the economy as a whole. And the root cause of this crisis long preceded the pandemic: The expectations for the American worker and the American parent are inherently contradictory — and something’s got to give. What happens next may significantly shape what the future of work is like for millions of Americans.

“It’s so in everyone’s face right now, because you’re on Zoom calls and you see kids in the background because your coworker has caregiving responsibilities,” Jasmine Tucker, director of research at the women’s advocacy group National Women’s Law Center, said. “If this pandemic hasn’t laid bare that this is a real problem that needs to be addressed, then when is it going to be more clear?”

The paradigm of the ideal worker who’s completely available for work is predicated on the notion that someone else (typically a female spouse) will take care of child care and domestic labor.

“The ideal worker norm tells you that you have to be dedicated to your job 24-7, you have to have your cell phone with you at all times, you have to be constantly available for email, you have to be ready to drop everything to finish that report. Essentially, you’re supposed to be dedicating your whole life to your work,” Jessica Calarco, an associate professor of sociology at Indiana University, told Recode. “Simultaneously, the ideal motherhood norm tells mothers that they are supposed to be dedicating their entire lives to their children, that they’re supposed to be willing to drop everything to meet their kids’ needs and to make sure that their kids’ well-being is put before all other things.”

These expectations have only intensified over time. In the past several decades, highly educated and highly paid workers have been putting in even more hours. That’s especially insidious in America, where people already work more hours than in most other industrialized nations. The pandemic, again, made an already untenable situation even worse. Americans working from home put in somewhere between an extra hour to an extra three hours of work per day last spring.

“I always need to be available for my team, clients, and also reporters, in addition to the day-to-day work that needs to be done,” Lauren Perry, a vice president at a PR agency who’s based in Massachusetts and who has a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old, said. To keep up, she multitasks and misses sleep.

Her mother’s generation had it different, she says.

“I see a really stark difference in how we work from simply looking at the number of hours,” Perry said. “While she limited her work to fit only within the hours her kids didn’t need her, I am constantly working and even looking for more time to give to my career.”

Overwork, which can be defined as working 50 or more hours per week, has contributed to maintaining the pay gap between men and women, despite women having achieved higher levels of education.

“When you zoom out to think about who can actually do that, who’s best poised to live up to that ideal in a way that would reward them in the workplace, it’s men,” Caitlyn Collins, an assistant professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis and author of Making Motherhood Work, told Recode. They’re more likely to be able to devote their time to work rather than child care, and are compensated by their jobs accordingly.

And because many women in heterosexual partnerships are making less money, that often pushed them to take on an even larger portion of child care and housework than they already disproportionately shouldered.

“I felt like I had to be in a million different places at once: preschool on Zoom, my own Zoom meetings, and taking care of household duties,” Michelle Pietsch, a vice president of revenue at a software company and a mother of two toddlers in Boston, said. “There was no escape.”

That hasn’t stopped many working women from trying even harder.

“There is a whole term for what happens to women as they become mothers, and ‘the mommy track’ isn’t a compliment,” Martha Shaughnessy, a founder of a PR agency and a mother with two young children based in San Francisco, said. “Knowing there’s a pejorative term for what a male-dominated workforce thinks of working moms leads to pressure to be better and do more than male or non-mother peers.”

Working from home and work-from-home technology have been a double-edged sword for working mothers: It gives women the opportunity to actually do their outsized share of labor.

“While there’s no expectation for me to be responding to emails at all hours, I often feel the need personally to ‘get ahead’ or respond to colleagues in other geographies through email response in the evening after my kids are asleep,” Brenna Fitzgerald, a vice president of corporate communications in Boston and a mother to a 6-year-old and a 3-year-old, said. “It was a constant struggle to navigate trying to excel at work, take the best care of my children, be a partner to my husband, and clean up the hundreds of toys (and Legos, so many Legos) that were used each day.”

Parenting has also become more intense in recent decades, with mothers spending an extra hour each day with their kids than mothers did back in the 1960s.

Indiana University’s Calarco said mothers’ increasing attentiveness to their children stems from a cultural backlash to women’s growing prominence in the workforce, beginning in the 1990s.

“If you have women in the workforce in large numbers, they begin to be able to compete with men for positions and top jobs,” Calarco explained. “So if men want to maintain power and status in society, they have an interest in telling women to go back home.”

What ensued was societal messaging that glorified motherhood — the more involved, the better. During the pandemic, research showed Americans have shifted toward a more conservative view on women: They are increasingly likely to say mothers should parent young children and stay at home. The same study also found, confusingly, that people increasingly think mothers should make money.

“Amongst middle-class families there’s this assumption that parenting should be very intensive — time-intensive, as well as emotionally intense and financially intense,” Washington University’s Collins told Recode. (She added that unrealistic portrayals of motherhood on social media are also partly to blame.)

Whatever the reason, women are expected to schedule almost every minute of their children’s lives.

“When I was younger it was okay, and even expected, to just send your kids outside to roam the neighborhoods with friends and come home for dinner,” Whitney Hoffman-Bennett, a vice president of talent at a marketing platform in Atlanta and a mother of three, said. “Now parents are judged for this type of behavior.”

She added, “It’s no wonder parents are burnt out, when some parents feel an expectation to work like they don’t have children, and parent like they don’t have a job.”

Several of the mothers Recode interviewed described guilt when their need to work interfered with their need to parent.

“When I felt okay about my workload, I felt guilty that I wasn’t having meaningful face time with my daughter,” Amanda Reed, an account supervisor in Austin, Texas, and a mother of a 4-year-old and a 9-month-old, said. “When she and I would have a good day, I was hyperaware of the work that I was procrastinating on, or worried that I wasn’t meeting expectations at work.”

Despite all the extra labor, most of the women we spoke to said the best part of working from home during the pandemic was the extra time they got to spend with their children.

But Calarco sees that viewpoint as a salve for a situation that’s not quite fair.

“When you’re in a tough position, when you’re forced to make a choice that isn’t ideal, oftentimes, you’ll find a silver lining and you’ll find a thing to look to that allows you to feel good about that choice,” Calarco said.

“Because we have these cultural norms that tell women that they should be at home with their kids, it’s easy for them to turn to those norms and say, ‘Hey, look, I got to fulfill the norm, I got to do this thing that society has told me I’m supposed to be doing, to be there for my kid.’”

Most of the women Recode spoke with said the pressure to be good workers and good parents was self-enforced. However, it’s also true that most insidious power structures can be difficult to isolate from personal preference.

“Americans don’t want to think that anyone is influencing them to do anything. That’s deeply problematic, because first of all, it’s not true,” Collins said. “Second of all, when women think that they are only putting pressure on themselves, and then they can’t live up to those expectations, they blame themselves.”

She added, “In fact, the cards are stacked against them. They’re operating within a system that is not set up to support them.”

Cultural norms don’t exist in a vacuum. And you can’t just wish them away.

Changing the unfair situation for working mothers in American requires structural change that’s so far happened very slowly. It means paying women the same as men, so that their careers don’t come second practically by default. It also requires valuing child care more in the first place. The future of the economy hinges on child care, and yet we pay child care workers — who are mostly women — less than $11 an hour.

The child care system in America is also overextended and can be prohibitively expensive, so it also needs to become more available and affordable. Millions of Americans live in child care “deserts” where the number of kids exceeds the number of slots available to care for them.

”It really isn’t possible to have a full-time, busy career and also take care of your children full-time,” Fitzgerald said. “Child care was really the only thing that made my situation better.”

Experts told Recode one of the core solutions to the crisis the US is facing would be to offer universal, high-quality child care starting for kids at a very young age.

The Biden administration is working on it.

Its American Rescue Plan, which was signed into law in March, set aside $40 billion to help bail out the struggling child care industry. The plan also gives parents a child tax credit of up to $300 a month per child — not enough to pay for full-time child care, but certainly helpful — and advocacy groups are hoping that benefit will continue indefinitely.

Biden’s American Families Plan could extend that benefit and go further, but the plan still needs to make it through Congress. It would create universal free preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds and make child care more affordable for people with low incomes. The plan would also create a national paid family leave, which would give mothers and fathers more time off to care for their babies. Collins says it’s important that paid leave cover a high portion of people’s pay so that they’re more likely to take it.

As National Women’s Law Center’s Tucker put it, “If we want women to come back to the labor force, then we’re going to have to make it so that they can afford to do so.”

As for making work more hospitable for working mothers, many are advocating for remote work and flexible schedules to continue being an option when the pandemic is eventually over.

Flexible work schedules, where women can duck out in the middle of the day to pick up a sick kid or get some chores done, aren’t a panacea, but they are a way to help women balance their conflicting demands. Women have long clamored for the ability to work from home and are more likely than men to want the privilege. More flexibility, reduced working hours, and more paid time off are the top benefits that people who voluntarily left the workforce said would make them return, according to a new study by Qualtrics, a company that surveys employees.

And there are hopeful signs that at least some companies are taking these issues seriously.

Elise Freedman, workforce transformation leader at management consulting firm Korn Ferry, says the “vast majority” of Fortune 1000 companies have put programs in place to help them retain and attract their female employees.

“There’s been a lot of research that talks about diversity in general, but even specifically women in leadership roles, and how that can [positively] impact culture and financial results,” she said. “So organizations are very focused on that.”

For now, mothers are dependent on a fraught child care system and work culture and policies that are often stacked against them.

“I really hoped that the silver lining was coming, that there would be some more structural change,” Danowski said. “I’m not really seeing that.” She does, however, take solace in the next generation.

“Their values are just different: they are the ones that leave the office a little after five, they don’t stay late, they are better at setting boundaries. I see the men taking paternity leave,” she said. “So I’m hopeful there’s some attitude changes, that people have just had enough.”

source https://www.vox.com/recode/22605612/working-mothers-pandemic-childcare-ideal-parent-worker-remote

Post a Comment