My first encounter of a teenager with a weapon was when I was a 23-year-old intern providing services at a youth foster home. I received a call from a foster mother about a dispute that occurred between two teens. I could hear them yelling and cursing at each other in the background, and I told the mother to put me on speaker so that I could talk to them as I was driving over.

On the phone, I calmly asked the teens questions intended to distract them away from the dispute. “Did you eat today?” “Don’t you have soccer practice in a bit?” and “You’re holding a brick?! Okay, Bob the Builder, where did you find that?!” As I entered the house, I concealed my badge — some people tend to distrust anyone resembling authority, and this fear often presents as anger, which is then misinterpreted as a threat. The teens were standing in the bedroom, one with a knife and the other a brick, ready to fight.

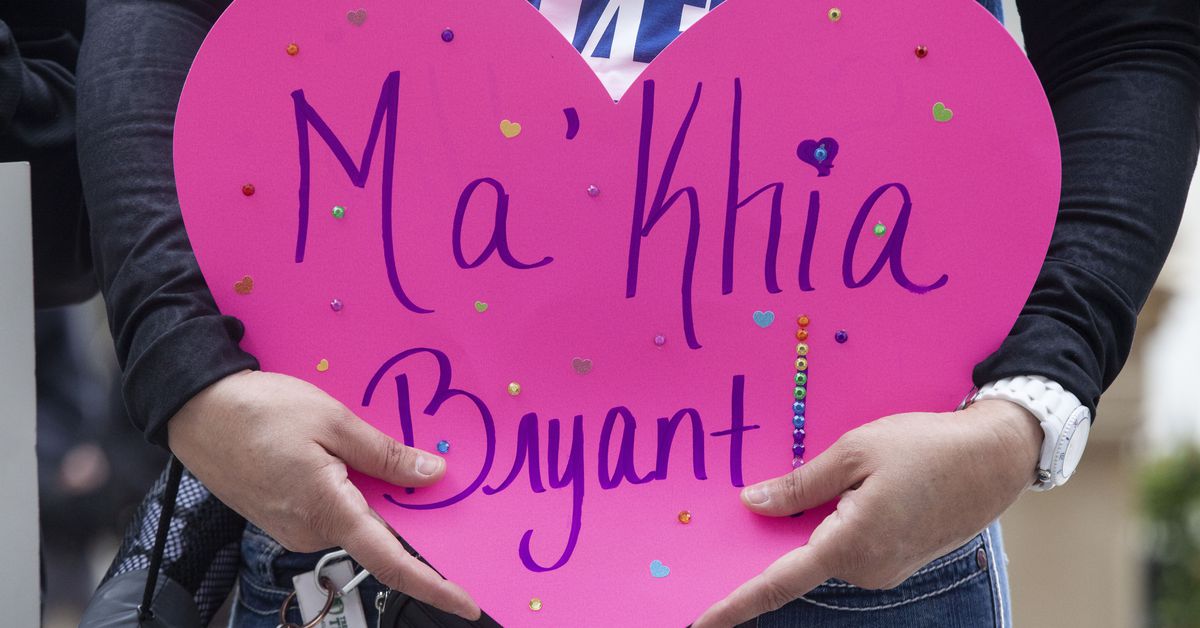

It was undoubtedly a scary situation, and someone could have been hurt. But I knew as a trained professional that employing nonviolent deescalation techniques was not only possible but necessary to stop an aggressive interaction from becoming violent or even fatal. The goal is to provide crisis intervention services and keep kids safe — and avoid any ending up like Ma’khia Bryant, the 16-year-old Black girl who was shot by a police officer last week while wielding a knife.

Inside the house, I did not yell, nor did I order the teens to drop their weapons. Instead, I asked whether they wanted something to eat. Confused and suddenly distracted by me, neither responded, but when I walked over to the kitchen and started making them food, they followed me.

As I made them sandwiches, I asked them to help me with tasks, such as working together to set the table. I initially had them talk directly to me and not to each other. After a few minutes, both teens had left their weapons on the counter and were helping. Once emotions were regulated, we talked through the initial issue and resolved it, making a plan with the foster mom and my clinical supervisor about what to do should this happen again in the future.

These are techniques I have practiced for years with much success, as a psychologist who has worked in clinical and forensic settings providing psychological services in homes, shelters, schools, streets, clinics, crisis residential centers, psychiatric hospitals, and county jail. I have served children, teenagers, and adults living with a severe and persistent mental illness, such as conduct disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and co-occurring substance use disorders.

On occasion — as a result of their mental health, lack of support because of societal stigmatization, and a lack of resources that would ordinarily allow them to independently survive and thrive in society — these individuals present with aggression and an inability to self-regulate their emotions and, consequently, engage in behaviors that can seem aggressive or involve weapons. But these are not situations that require or should be met with violent force.

So, when I read the news about Ma’Khia Bryant, my heart sank. The family of Bryant described her as a beautiful, sweet, and good student who had recently earned her place on the honor roll and was looking forward to soon leaving foster placement to reunite with her biological mother. Although we do not know the exact circumstances, it was reported that Bryant placed the 911 call herself because she felt threatened over a dispute related to household chores. The horror of the taking of such a young life should be dominating national headlines. Yet, much of the reaction seems to be a “debate” or justification about the use of force given that Bryant was wielding a weapon.

These narratives are attempts to displace blame onto the victim and their family rather than on the systems that created situations that led to her death. The blame is swiftly placed on the young Black girl — or Black man, or Hispanic boy — but not the police officer who caused the fatality.

We do not instinctively question or validate Bryant’s vulnerability or fear. We do not consider how scared she must have been to reach the point of calling law enforcement for help in her own home. We do not ask ourselves if the police could have attempted any form of deescalation that didn’t involve shooting a teenager. It is worth considering whether Bryant might have still been alive today if a mental health expert — or someone else trained in nonviolent deescalation — had responded to the call.

My experience outlined here is not meant as clinical advice or guidance. But I do believe that psychologically informed approaches can be applied to escalated situations that so often end in aggressive police encounters. Mental health experts are trained in deescalating without resorting to violence by using techniques such as building clinical rapport in any environment, compassionately engaging with individuals presenting with emotional and behavioral distress, and utilizing distractions and humor in volatile situations to mitigate aggressive blow-ups. We do all of this while simultaneously evaluating danger of imminent harm to self or others.

Various cities and counties in the US have taken concerted steps to introduce mental health experts into crisis response in order to reduce an overwhelming law enforcement presence when responding to community calls for help. Seattle deploys a crisis response team during crisis situations and pairs mental health professionals with specially trained officers. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department does something similar in which they send out their medical evaluation team comprised of a trained deputy and a mental health expert.

A recent success story is Santa Barbara. In 2020, the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office Behavioral Sciences Unit and the Santa Barbara Police Department, in coordination with the Santa Barbara County Department of Behavioral Wellness, fielded 1,606 crisis calls. Of those, 20 cases resulted in arrests and zero resulted in death. This pilot program — in which a deputy is paired with a mental health professional who is employed and trained by the Department of Behavioral Wellness — exceeded expectations. It’s an approach that not only reduces arrests but also supports individuals with voluntarily engaging in mental health services.

If we are concerned about public safety, then we need to prioritize investing in mental health resources such as co-response teams and preventative community-led supportive services. We need to acknowledge how unjust policies and practices have created a level of privilege for some and oppression for many others. We need to remove systemic barriers that make it difficult for people to access financial, educational, occupational, medical, and mental health services so that we are not continuously responding to crises that far too often result in deaths. Ma’Khia Bryant didn’t have to die.

Merushka Bisetty is a psychologist and adjunct professor of psychopathology at Antioch University Santa Barbara. Her areas of expertise include providing culturally sensitive psychological services to marginalized children and adults diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illnesses.

source https://www.vox.com/first-person/22409527/makhia-bryant-deescalation

Post a Comment